- Research

- Open access

- Published:

Authoritarian leadership and task performance: the effects of leader-member exchange and dependence on leader

Frontiers of Business Research in China volume 13, Article number: 19 (2019)

Abstract

This study examines how and when authoritarian leadership affects subordinates’ task performance. Using social exchange theory and power dependence theory, this study proposes that authoritarian leadership negatively influences task performance through leader-member exchange (LMX). This study further proposes that the effect of authoritarian leadership on LMX is stronger when a subordinate has less dependence on a leader. A two-wave survey was conducted in a large electronics and information enterprise group in China. These hypotheses are supported by results based on 219 supervisor-subordinate dyads. The results reveal that authoritarian leadership negatively affects subordinates’ task performance via LMX. Dependence on leader buffers the negative effect of authoritarian leadership on LMX and mitigates the indirect effect of authoritarian leadership on employee task performance through LMX. Theoretical contributions and practical implications are discussed.

Introduction

The dark or destructive side of leadership behavior has attracted the attention of many scholars and practitioners in recent years (Liao and Liu 2016). Much of the research has focused on authoritarian leadership (e.g., Chan et al. 2013; Li and Sun 2015; Schaubroeck et al. 2017), which is prevalent in Latin America, the Middle East, and Asia-Pacific business organizations (Pellegrini and Scandura 2008). Authoritarian leadership refers to the leadership that stresses the use of authority to control subordinates (Cheng et al. 2004). In general, authoritarian leadership has a negative connotation in the literature; this type of leadership is negatively related to employees’ attitudes, emotions and perceptions, for example, regarding organizational commitment, job satisfaction, tacit knowledge-sharing intentions (Chen et al. 2018), team identification (Cheng and Wang 2015), intention to stay and organizational justice (Pellegrini and Scandura 2008; Schaubroeck et al. 2017). A substantial body of empirical research has also explored the influence of authoritarian leadership on followers’ work-related behavior and outcomes. Authoritarian leadership is negatively related to employee voice (Chan 2014; Li and Sun 2015), organizational citizenship behavior (Chan et al. 2013), employee creativity (Guo et al. 2018), and employee performance (Chan et al. 2013; Schaubroeck et al. 2017; Shen et al. 2019; Wu et al. 2012), and such leadership is positively associated with employee deviant workplace behavior (Jiang et al. 2017). In particular, studies concerning authoritarian leadership and employee performance have suggested that authoritarian leadership is negatively related to employee performance because subordinates of authoritarian leaders are likely to have low levels of the following: trust-in-supervisor, organization-based self-esteem, perceived insider status, relational identification, and thus, little motivation to improve performance (Chan et al. 2013; Schaubroeck et al. 2017; Shen et al. 2019; Wu et al. 2012).

Although previous studies have explored the effect of authoritarian leadership on employee performance from the perspective of self-evaluation or perception, such as organization-based self-esteem or perceived insider status, the underlying mechanism remains unclear (Chan et al. 2013; Schaubroeck et al. 2017). To fully understand the effect of authoritarian leadership on employee performance, it is critical to investigate alternative influencing mechanisms of authoritarian leadership from other perspectives (Hiller et al. 2019). For example, Wu et al. (2012) reveal that trust-in-supervisor mediates the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employee performance; Shen et al. (2019) show that relational identification also mediates this relationship. These findings suggest that authoritarian leadership may lead to a poor exchange between leaders and followers, whereby followers of authoritarian leaders may reciprocate by withholding their efforts at work. These studies use a social exchange perspective to understand the effect of authoritarian leadership on employee performance but fail to examine the exchange relationship explicitly. To summarize, little is known about how authoritarian leadership impacts the ongoing social exchange relationship between leaders and subordinates and how such social exchange affects subordinates’ performance. Therefore, we adopt a social exchange perspective to explore the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employee task performance to gain a deep understanding of employees’ reaction to authoritarian leadership behavior.

From the perspective of social exchange, leader-member exchange (LMX) is most often chosen to examine how leadership affects followers’ behavior and outcomes (Dulebohn et al. 2012). Thus, we specifically posit that LMX mediates the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employee task performance.

Moreover, Wang and Guan (2018) suggest that the effects of authoritarian leadership on employees depend on certain conditions and, thus, may influence the relationship between authoritarian leadership and performance. Literature concerning the relationship between mistreatment and employees’ response find that employees are less likely to respond to perceived mistreatment with deviant behavior when their power status is lower than that of the offender or when they depend more on the perpetrator (Aquino et al. 2001; Tepper et al. 2009). Since employees have less power than the offender, vengeful or deviant employee behavior may incur a punitive response or trigger future downward hostility (Tepper et al. 2009). Thus, the second purpose of this research is to examine how subordinates’ dependence on a leader impacts the responses of subordinates to authoritarian leadership. Specifically, we posit that subordinates’ dependence on a leader moderates the relationship between authoritarian leadership and LMX.

By examining the relationship between authoritarian leadership and subordinates’ task performance, this research makes several contributions to the literature. First, we directly examine the social exchange relationship between authoritarian leaders and their subordinates, which helps further clarify the mediating mechanism of authoritarian leadership on employee task performance (Chan et al. 2013; Schaubroeck et al. 2017). Second, this study contributes to the LMX literature by exploring the role of LMX in destructive or dark leadership. Indeed, most studies on LMX focus on how constructive leadership leads to a positive and high-quality LMX relationship, which then impacts followers’ behavior and outcomes (Chan and Mak 2012; Lin et al. 2018; Qian et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2005). Therefore, exploring and determining how destructive or dark leadership behavior influences the exchange relationship between leaders and followers is imperative (Harvey et al. 2007; Xu et al. 2012). Third, this study helps clarify the boundary condition of the effect of authoritarian leadership on subordinate outcomes. By investigating and demonstrating the moderating effect of employee dependence on a leader, our research offers some of the first insights into how dependence influences the effect of authoritarian leadership and the social exchange relationship as well.

Theoretical background and hypotheses development

Authoritarian leadership

Authoritarian leadership refers to leader behavior that exerts absolute authority and control over subordinates and demands unconditional obedience (Farh and Cheng 2000; Pellegrini and Scandura 2008). Authoritarian leaders expect their subordinates to obey their requests without disagreement and to be socialized to accept and respect a strict and centralized hierarchy (Redding 1990).

Authoritarian leadership reflects the cultural characteristics of familial ties, paternalistic control, and submission to authority in Chinese culture (Farh and Cheng 2000; Farh et al. 2008). Influenced by Confucian doctrine, a father has absolute authority and power over his children and other family members in a traditional Chinese family (Cheng and Wang 2015). In business organizations, leaders often enforce this patriarchal value by establishing a vertical hierarchy and by playing a paternal role in an authoritarian leadership style (Peng et al. 2001). Authoritarian leadership is prevalent in Chinese organizations and its construct domain remains relatively unchanged regardless of rapid modernization (Farh et al. 2008).

According to Farh and Cheng’s (2000) research, authoritarian leadership has four kinds of typical behavior. First, authoritarian leaders exercise tight control over their subordinates and require unquestioning submission. To maintain their absolute dominance in organizations, authoritarian leaders are unwilling to empower their subordinates. In addition, higher authoritarian leaders share relatively little information with employees and adopt a top-down communication style. Second, authoritarian leaders tend to deliberately ignore subordinates’ suggestions and contributions. Such leaders are more likely to attribute success to themselves and to attribute failure to subordinates. Third, authoritarian leaders focus very much on their dignity and always show confidence. Such leaders control and manipulate information to maintain the advantage of power distance and create and maintain a good image through manipulation. Fourth, highly authoritarian leaders demand that their subordinates achieve the best performance within the organization and make all the important decisions in their team. In addition, such leaders strictly punish employees for poor performance.

Authoritarian leadership and task performance

In this study, we posit that authoritarian leadership harms employee performance according to the four kinds of typical behavior of authoritarian leaders. First, authoritarian leaders try to maintain a strict hierarchy, are unwilling to share information with followers, and adopt a top-down communication style (Farh and Cheng 2000). All of these behaviors create distance and distrust between subordinates and leaders, thus leading to poor employee performance (Cheng and Wang 2015). Second, authoritarian leaders tend to ignore followers’ contributions to success and to attribute failure to followers (Farh and Cheng 2000). These behaviors greatly undermine subordinates’ self-evaluation and are harmful to improving employee performance (Chan et al. 2013; Schaubroeck et al. 2017). Third, it is typical for leaders with an authoritarian leadership style to control and manipulate information to maintain the advantage of power distance and create and maintain a good image (Farh and Cheng 2000). Such behaviors set a bad example for subordinates and are not conducive to improving employee performance (Chen et al. 2018). Fourth, leaders with a highly authoritarian leadership style focus strongly on the supreme importance of performance. Subordinates are commanded to pursue high performance and surpass competitors. If subordinates fail to reach the desired goal, leaders will rebuke and punish them severely (Farh and Cheng 2000). Leaders’ emphasis on high performance and possible severe consequences enhance subordinates’ sense of fear (Guo et al. 2018), which is detrimental to performance improvement. To summarize, we posit that authoritarian leadership is negatively related to employee performance.

Authoritarian leadership and LMX

Building on social exchange theory (Blau 1964), LMX refers to the quality of the dyadic exchange relationship between a leader and a subordinate and the degree of emotional support and exchange of valued resources (Graen and Uhl-Bien 1995; Liden and Maslyn 1998; Wayne and Green 1993). Low-quality relationships are characterized by transactional exchanges based on employment contracts. High-quality relationships are characterized by affect, loyalty, perceived contribution and professional respect (Dienesch and Liden 1986; Liden et al. 1997; Liden and Maslyn 1998). There are several reasons why authoritarian leadership is related to a lower quality of LMX. First, since authoritarian leaders demonstrate authoritarian behaviors, such as controlling information, maintaining a strict hierarchy and high power distance, ignoring followers’ contributions and suggestions, and attributing losses to subordinates and punishing them, employees who perceive highly authoritarian leadership tend to strongly fear their leaders (Guo et al. 2018). These employees follow their leaders because of the need to work instead of affective commitment, which is a relationship based on an employment contract and leads to lower LMX. Second, subordinates of authoritarian leaders are less likely to identify with their leaders and teams because these leaders focus on obtaining the best performance from their subordinates while controlling information. Without identification with their leaders and teams, employees can hardly be loyal to their leaders and can be less motivated to maintain high-quality relationships with them, thus leading to lower LMX. Third, both authoritarian leaders and their subordinates perceive that the other contributes little to the performance of the team. Authoritarian leaders tend to ignore subordinates’ advice and contributions, while the subordinates perceive that leaders contribute little because they focus more on controlling information and maintaining the hierarchy instead of helping subordinates attain high performance (Farh and Cheng 2000). Fourth, since authoritarian leaders and their subordinates each perceive that the other contributes little, they cannot sincerely show professional respect to each other, thereby leading to lower LMX (Liden and Maslyn 1998). Therefore, we expect a negative relationship between authoritarian leadership and LMX.

Hypothesis 1: Authoritarian leadership is negatively related to LMX.

Authoritarian leadership, LMX, and task performance

As described by Blau (1964), unspecified obligations are very important in social exchange. When one person helps another, some future return is expected, though it is often uncertain when it will happen and in what form (Gouldner 1960). The premise of social exchange theory is that in a dyadic relationship (e.g., leader and follower), something given creates an obligation to respond with behavior that has equal value (Gouldner 1960; Perugini and Gallucci 2001). According to social exchange theory, high-quality LMX is considered as rewards or benefits from the leaders for the employees. This may create obligations for the employees to reciprocate with equivalent positive behaviors to maintain the high quality of the LMX (Blau 1964; Emerson 1976). Since one of the requirements and expectations from authoritarian leaders is high task performance (Cheng et al. 2004; Farh and Cheng 2000), after perceiving a high LMX as involving the receipt of rewards and benefits from the leader, employees with high-quality LMX are more likely, in return, to consider high task performance as a way to meet supervisors’ requirements and expectations. Here, the exchange currency of employees to reciprocate the rewards and benefits from their leaders is to pursue high task performance. The desire to reciprocate may motivate subordinates to exert more effort in achieving high task performance. Conversely, where there is low-quality LMX, subordinates are not obligated to increase effort to benefit supervisors and organizations (Gouldner 1960). In addition, according to the principle of negative reciprocity, which states that those who receive unfavorable treatment will respond with unfavorable behaviors (Gouldner 1960), because subordinates of authoritarian leaders receive unfavorable treatment, such as being strictly controlled and being compelled to obey unconditionally, these subordinates may respond with undesirable behaviors, such as withholding their effort and engaging in more deviant workplace behavior (Jiang et al. 2017).

To summarize, the typical behaviors of authoritarian leaders produce low-quality LMX. Consequently, subordinates do not feel obligated or motivated to strive for high task performance. In accordance with the principle of negative reciprocity, subordinates even engage in deviant workplace behavior, and employee task performance decreases. Therefore, authoritarian leadership is likely to be negatively related to employee task performance by creating low-quality LMX.

Hypothesis 2: LMX mediates the negative relationship between authoritarian leadership and subordinates’ task performance.

The moderation of subordinate dependence on leader

This study posits that the relationship between authoritarian leadership and LMX is moderated by dependence on a leader. Studies that investigate revenge and retaliation in organizations reveal that employees may be constrained in responding to perceived mistreatment with deviant behavior when their power status is lower than the offender and when they are largely dependent on their leaders (Aquino et al. 2001; Tepper et al. 2009). Therefore, the corresponding behavior of subordinates is affected by their dependence on their leaders and by the power relationship between them. The effect of dependence can be explained from a power dependence perspective. According to Emerson’s (1962) power dependence theory, dependence of individuals on others makes the former relatively powerless. In contrast, individuals on whom others depend but who do not depend on those others in return are relatively powerful. The powerful have many benefits, such as being able to reserve support or to exit from relationships at lower costs than the less powerful (Cook and Emerson 1978; Giebels et al. 2000), having more transaction alternatives (Brass 1981), and being able to engage in counter-revenge against the less powerful (Aquino et al. 2006). Therefore, taking their future conditions into consideration, those with greater dependence or less power are restricted from performing behaviors that are in their self-interest (Molm 1988).

This dependence and power relationship between leaders and their followers can be captured by the construct of “subordinate dependence on leader.” It refers to subordinates’ material and psychological dependence on leaders because subordinates believe that only by obeying their leader can they obtain the necessary work resources and support (Chou et al. 2005). We posit that subordinate dependence on leader moderates the relationship between authoritarian leadership and LMX. Specifically, a leader’s authoritarian behavior is rooted in the dependence of subordinates, that is, the dependence of subordinates rationalizes and strengthens the authoritarian leadership of superiors (Cheng et al. 2004; Farh and Cheng 2000). In circumstances where employees are highly dependent on their leaders, authoritarian leaders control much valuable information and many resources related to subordinates’ competence and development at work. Taking their future conditions into consideration, subordinates are more likely to be obedient. These reluctant employees take conciliatory action or withhold their anger and respond with desirable behaviors to meet the requirements and expectations of leaders, thereby hoping to have good relations with supervisors and maintain a high relationship quality. In contrast, subordinates who have a low dependence on their leaders tend to act self-interestedly. Such subordinates are not motivated to meet the expectations of authoritarian leaders at the cost of harming their self-interest, such as their self-esteem, and the relationship with the leader becomes worse. These arguments produce a moderation prediction:

Hypothesis 3: Subordinate dependence on leader moderates the negative relationship between authoritarian leadership and LMX such that this negative relationship is weaker in cases where subordinate dependence on leader is higher.

Based on the above argument, we further propose that subordinate dependence on leader will moderate the indirect effect of authoritarian leadership on employee task performance through LMX. Subordinates with high levels of dependence on their leader will have higher LMX under authoritarian leadership; thus, they are more likely to work to reciprocate rewards or benefits provided by leader and to get more valued resources, thereby increasing their task performance. In contrast, those with low levels of dependence on leader reciprocate less and have fewer resources, since they do not develop high-quality relationships with their authoritarian leaders, and will not improve their task performance. Thus, we hypothesize the following:

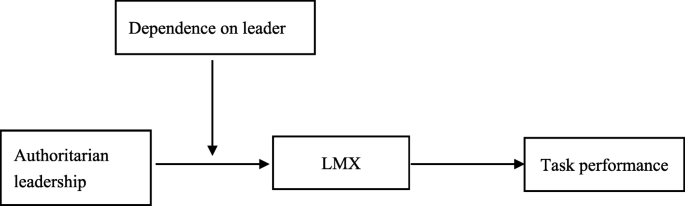

Hypothesis 4: The indirect relationship between authoritarian leadership and task performance through LMX is stronger for those with lower dependence on leader. Figure 1 depicts the conceptual model.

Method

Research setting, participants, and procedures

This research was conducted in a large electronics and information enterprise group in China. Under the permission of the companies’ directors, we met with the companies’ personnel directors and explained the study objectives. The personnel directors helped us contact group supervisors and each group supervisor was instructed about the study objectives and procedure.

We used two sets of questionnaires to minimize common method bias: one for subordinates and the other for their immediate supervisors. First, we delivered surveys to employees (time 1). During the survey, we explained the purpose of the study and noted that participation was voluntary and their responses would be kept confidential. This survey included questions about measures of subordinates for their immediate supervisor’s authoritarian leadership, self-reported dependence on the leader, the LMX relationship and personal information. After 2 months, we administered questionnaires to supervisors to obtain their assessments of subordinates’ task performance (time 2).

Data on a total of 258 supervisor-subordinate dyads were collected. Among these responses, 20 cases were not included in the analysis because they could not be reliably matched. Nine cases were excluded because the supervisors’ rating of task performance was missing. In the other 10 cases, the reaction tendency was very obvious. These omissions resulted in a final sample set of 219 supervisor-subordinate dyad data. An independent t test was used to examine the difference between the final sample and the dropped sample in terms of demographic features. The results show that there is no significant difference between these two samples in terms of demographic features.

In the sample, 68.9% were male; 68.5% were Chinese. As for age distribution, 31.1% were aged 30 or younger; 63.9% were aged between 31 and 50; 5.0% were aged 51 or older. 83.6% of the employee respondents had received at least a college education. The mean tenure of the employee respondents was 6.42 years.

Measures

All scales used in this study are widely accepted by the academic community. Because participants were recruited from 18 companies in China and from overseas, it was necessary to have scales in both languages. Translation and back-translation procedures were followed to translate the English-based measures into the corresponding Chinese-English comparison scales.

Authoritarian leadership. Authoritarian leadership was measured using the nine-item scale developed by Cheng et al. (2004) at time 1. Authoritarian leadership has two dimensions: Zhuanquan and Shangyan. Zhuanquan stresses the use of authority to control subordinates and subordinates’ unquestioning compliance. Shangyan emphasizes the strict discipline and the supreme importance of high performance (Cheng et al. 2004; Chen and Farh 2010; Li et al. 2013). A sample item is “Our supervisor determines all decisions in the organization whether they are important or not” (α = 0.90). All items used six-point Likert-type response categories (ranging from 1 = few to 6 = very frequent).

LMX. LMX was measured at time 1 and each subordinate described the quality of his/her exchange relationship with the leader. We used the seven-item scale developed by Scandura and Graen (1984). A sample item is “My line manager is personally inclined to use power to help me solve problems in my work” (α = 0.88). All items used six-point Likert-type response categories (ranging from 1 = totally disagree to 6 = totally agree).

Subordinate dependence on leader. Subordinate dependence on leader was measured using the eight-item scale developed by Chou et al. (2005) at time 1. Subordinate dependence on leader has two dimensions: job dependence and affective dependence (Chou et al. 2005). A sample item is “I rely on my supervisor to obtain the necessary work resources (i.e., budget and equipment, etc.)” (α = 0.75). All items used six-point Likert-type response categories (ranging from 1 = totally disagree to 6 = totally agree).

Task performance. Subordinates’ task performance was measured using the four-item scale at time 2 (Chen et al. 2002). Leaders rated their subordinates’ performance respectively. A sample item is “Performance always meets the expectations of the supervisor” (α = 0.91). All items used six-point Likert-type response categories (ranging from 1 = totally disagree to 6 = totally agree).

Control variables. This study controls for the age, gender and tenure of the subordinates. These demographic variables are widely used as control variables in the study of authoritarian leadership mechanisms (e.g., Li and Sun 2015; Wang and Guan 2018). Gender was coded as 0 = male and 1 = female. Age and tenure were measured by the number of years.

Results

Confirmatory factor analyses

We conducted confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) in Mplus 7 to test the distinctiveness of the variables included in the study: authoritarian leadership, LMX, subordinate dependence on leader, and employee task performance. To reduce the model size, we created two parcels based on the two subdimensions of authoritarian leadership to indicate the factors of authoritarian leadership. In addition, we created two parcels based on the two subdimensions of subordinate dependence on leader. As indicated in Table 1, the hypothesized four-factor model fits the data well: χ2(df = 84) = 181.29, RMSEA = 0.07, SRMR = 0.06, CFI = 0.94, and TLI = 0.92. Against this baseline model, we test three alternative models: a three-factor model combining authoritarian leadership and LMX into one factor; a two-factor model combining authoritarian leadership, LMX and subordinate dependence on leader into one factor; and a single-factor model combining all four variables into one factor. As shown in Table 1, the hypothesized four-factor model fits the data significantly better than all three alternative models, indicating that the four variables show good discriminant validity. Thus, we retained the hypothesized four-factor model for our analyses.

Descriptive statistics

We present the means, standard deviations, and correlations among all the variables in Table 2. The results show that authoritarian leadership is negatively related to LMX (r = − 0.26, p < 0.01) and employee task performance (r = − 0.22, p < 0.01). The results also support that there is a positive relationship between LMX and employee task performance (r = 0.25, p < 0.01).

Hypotheses testing

We performed a mediation and moderation analysis to further examine the joint effects of authoritarian leadership, LMX, and subordinate dependence on leader on employee task performance. More specifically, to test the four hypotheses, we tested moderated mediation models using conditional process analysis. Conditional process analysis is an integrative approach that estimates the mediation and moderation effects simultaneously and yields estimates of the conditional indirect and conditional direct effects. Scores for authoritarian leadership and dependence on leader were mean centered in the following analysis to avoid the problem of multicollinearity when their interaction terms were included.

As shown in Table 3, after controlling for age, tenure and gender, authoritarian leadership has a negative relationship with LMX (B = − 0.27, SE = 0.08, p < 0.001) and employee task performance (B = − 0.21, SE = 0.06, p < 0.01). The positive relationship between LMX and employee task performance is also significant (B = 0.15, SE = 0.06, p < 0.05). The bootstrapping results further suggest that the indirect effect of authoritarian leadership on employee task performance via LMX is significant (indirect effect = − 0.04; SE = 0.02; 95% CI = [− 0.0922, − 0.0116], excluding zero). These findings support Hypotheses 1 and 2.

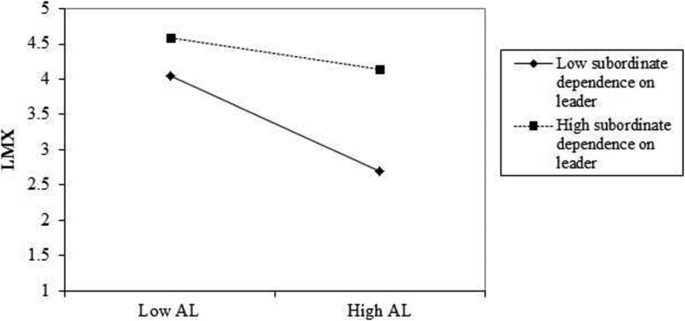

Hypothesis 3 proposes a moderating effect of subordinate dependence on the relationship between authoritarian leadership and LMX. We examined this hypothesis by adding an interaction term of authoritarian leadership and subordinate dependence on leader into the model. The results reveal that the predicted interaction is significant (B = 0.25, SE = 0.07, p < 0.001). To further interpret the nature of this significant interaction, we plotted the relationship between authoritarian leadership and LMX at 1 SD above and below the mean of the moderator. Figure 2 shows the moderating role of subordinate dependence on leader: When subordinate dependence on leader was higher, the negative effect of authoritarian leadership on LMX was weaker (B = − 0.21, t = − 2.67, p < 0.01), supporting our hypothesis. However, when subordinate dependence on leader was lower, the negative effect of authoritarian leadership on LMX was stronger (B = − 0.63, t = − 6.69, p < 0.001). Furthermore, we examined whether subordinate dependence on leader moderated the indirect effect of authoritarian leadership on employee task performance through LMX. The findings reveal that the indirect effect was significant in cases where subordinate dependence on leader was higher (B = − 0.03; SE = 0.02; 95% CI = [− 0.0867, − 0.0063], excluding zero), and the indirect effect was also significant in cases where subordinate dependence on leader was lower (B = − 0.10; SE = 0.04; 95% CI = [− 0.1768, − 0.0339], excluding zero). The moderated mediation index was 0.0358 (95% CI = [0.0084, 0.0748], excluding zero). Therefore, the results are consistent with Hypotheses 3 and 4.

Discussion and conclusion

Based on theories of social exchange and power dependence, this study investigates the relationship between authoritarian leadership and its negative effects on employee task performance. In examining a moderated mediation model with two-wave data collected from subordinates and their leaders, we find that authoritarian leadership negatively relates to task performance; LMX mediates the negative relationship; subordinate dependence on leader buffers the negative effect of authoritarian leadership on LMX and mitigates the indirect effect of authoritarian leadership on employee task performance through LMX.

Theoretical implications

These findings contribute to the literature on authoritarian leadership, LMX and task performance and expand our understanding of why authoritarian leadership harms task performance. In terms of literature on leadership, the results may represent the first attempt to understand the relationship between authoritarian leadership and task performance via LMX. A flourishing number of studies explain the relationship between authoritarian leadership and employee performance from the perspective of self-evaluation or perception (e.g., Chan et al. 2013; Schaubroeck et al. 2017). There is a need to explore the divergent influencing mechanisms of authoritarian leadership on employee performance from other perspectives. Our study contributes to the literature by directly introducing LMX as a mediating variable in the relationship between authoritarian leadership and task performance from a social exchange perspective.

In addition, we offer important contributions to the literature on LMX. Most previous research on LMX focuses on how constructive leadership leads to a high-quality leader-member exchange relationship, which then affects employee behaviors and outcomes (Chan and Mak 2012; Lin et al. 2018; Qian et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2005). With the increasing attention given to destructive or dark leadership in recent years (e.g., Liao and Liu 2016; Tepper et al. 2009), it is imperative to explore and determine how destructive or dark leadership styles impact the quality of the exchange relationship between leaders and followers (Harvey et al. 2007; Xu et al. 2012). We fill this void by investigating how authoritarian leadership creates a low-quality social exchange, thereby leading to worse task performance.

Our study also extends current knowledge about the negative relationship between authoritarian leadership and task performance by uncovering the mechanisms whereby this effect is amplified or attenuated. Based on power dependence theory (Emerson 1962), we introduce subordinate dependence on leader as a moderating variable into the model. Our research offers some of the first insights into how dependence and power between leaders and subordinates (e.g., subordinate dependence on leader) influence the effect of authoritarian leadership and the social exchange relationship between leaders and subordinates as well.

Practical implications

Our results also provide some suggestions for practice. First, our study observes that authoritarian leadership is related to lower levels of LMX and is, therefore, related to lower employee task performance. These relationships suggest the importance of curbing leaders’ authoritarian behavior. Organizations could invest in leadership training programs that help control negative leadership behavior, establish a high-quality exchange relationship between supervisors and subordinates and thus enhance subordinates’ task performance.

Second, programs aimed at strengthening exchange relationships between supervisors and subordinates may also be conducive to improving employee task performance, because LMX is an important predictor of performance. To develop a higher-quality LMX, organizations could hold more social activities for supervisors and followers, providing them with more opportunities to deeply interact.

Third, our test of the moderating effects of subordinate dependence on leader reveals that the negative relationship between authoritarian leadership and LMX is weaker for employees that highly depend on their leader, thus implying that work background influences the interaction between leaders and subordinates. In business organizations where employees depend less on their leaders, it is more urgent to curb authoritarian behavior; for those business organizations where employees depend more on their leaders, the negative effect of authoritarian leadership on LMX and task performance is attenuated, but authoritarian leadership still negatively affects LMX and performance. As a result, organizations should avoid using an authoritarian leadership style to boost their employee performance.

Limitations and future directions

This study has several limitations. First, the samples in this research were all obtained from the same subsidiary of a large electronics and information enterprise group, which is a relatively traditional business organization. Although it is beneficial to control the potential impacts of factors such as industry and organization, thereby increasing the internal validity of research findings while, at the same time, weakening their external validity, future research can further verify the conclusions of this research with different types of industries. Second, although we collected data from leaders and followers at two time points, it is difficult to draw any causal conclusions. To validate our suggested moderated mediation process, a longitudinal design is required. Third, we introduce LMX perceived by subordinates into the relationship between authoritarian leadership and task performance. It is also necessary to consider the role of LMX as perceived by leaders. It is interesting to explore whether LMX perceived by subordinates and LMX perceived by authoritarian leaders are the same or not and how they interact and affect the relationship between authoritarian leadership and work outcomes. Fourth, we explore how authoritarian leadership affects employee task performance from a social exchange perspective and specifically choose LMX as the mediator. It is possible that alternative mediating processes exist. Future research can verify the conclusions of this research by investigating alternative mediating processes simultaneously.

Availability of data and materials

Please contact author for data requests.

References

Aquino, K., Tripp, T. M., & Bies, R. J. (2001). How employees respond to personal offense: The effects of blame attribution, victim status, and offender status on revenge and reconciliation in the workplace. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 52–59.

Aquino, K., Tripp, T. M., & Bies, R. J. (2006). Getting even or moving on? Power, procedural justice, and types of offense as predictors of revenge, forgiveness, reconciliation, and avoidance in organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(3), 653–668.

Blau, P. M. (1964). Exchange and power in social life. New York, NY: Wiley.

Brass, D. J. (1981). Structural relationships, job characteristics, and worker satisfaction and performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 26(3), 331–348.

Chan, S. C. (2014). Paternalistic leadership and employee voice: Does information sharing matter? Human Relations, 67(6), 667–693.

Chan, S. C. H., Huang, X., Snape, E., & Lam, C. K. (2013). The Janus face of paternalistic leaders: Authoritarianism, benevolence, subordinates’ organization-based self-esteem, and performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 34(1), 108–128.

Chan, S. C. H., & Mak, W. M. (2012). Benevolent leadership and follower performance: The mediating role of leader-member exchange (LMX). Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 29(2), 285–301.

Chen, C. C., & Farh, J. L. (2010). Developments in understanding Chinese leadership: Paternalism and its elaborations, moderations, and alternatives. In M. H. Bond (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Chinese Psychology (pp. 599–622). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chen, Z. J., Davison, R. M., Mao, J. Y., & Wang, Z. H. (2018). When and how authoritarian leadership and leader renqing orientation influence tacit knowledge sharing intentions. Information & Management, 55(7), 840–849.

Chen, Z. X., Tsui, A. S., & Farh, J. L. (2002). Loyalty to supervisor vs. organizational commitment: Relationships to employee performance in China. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 75(3), 339–356.

Cheng, B. S., Chou, L. F., Wu, T. Y., Huang, M. P., & Farh, J. L. (2004). Paternalistic leadership and subordinate responses: Establishing a leadership model in Chinese organizations. Asian Journal of Psychology, 7(1), 89–117.

Cheng, M. Y., & Wang, L. (2015). The mediating effect of ethical climate on the relationship between paternalistic leadership and team identification: A team-level analysis in the Chinese context. Journal of Business Ethics, 129(3), 639–654.

Chou, L. F., Cheng, B. S., & Jen, C. K. (2005). The contingent model of paternalistic leadership: Subordinate dependence and leader competence. Paper presented at the meeting of the annual meeting of academy of management. Honolulu.

Cook, K. S., & Emerson, R. M. (1978). Power, equity, and commitment in exchange networks. American Sociological Review, 43(5), 721–739.

Dienesch, R. M., & Liden, R. C. (1986). Leader-member exchange model of leadership: A critique and further development. Academy of Management Review, 11(3), 618–634.

Dulebohn, J. H., Bommer, W. H., Liden, R. C., Brouer, R. L., & Ferris, G. R. (2012). A meta-analysis of antecedents and consequences of leader-member exchange: Integrating the past with an eye toward the future. Journal of Management, 38(6), 1715–1759.

Emerson, R. M. (1962). Power-dependence relations. American Sociological Review, 27(1), 31–41.

Emerson, R. M. (1976). Social exchange theory. Annual Review of Sociology, 2, 335–362.

Farh, J. L., & Cheng, B. S. (2000). A cultural analysis of paternalistic leadership in Chinese organizations. In J. T. Li, A. S. Tsui, & E. Weldon (Eds.), Management and organizations in the Chinese context (pp. 84–127). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Farh, J. L., Liang, J., Chou, L. F., & Cheng, B. S. (2008). Paternalistic leadership in Chinese organizations: Research progress and future research directions. In C. C. Chen & Y. T. Lee (Eds.), Leadership and Management in China: Philosophies, theories, and practices (pp. 171–205). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Giebels, E., De Dreu, C. K. W., & Van de Vliert, E. (2000). Interdependence in negotiation: Effects of exit options and social motive on distributive and integrative negotiation. European Journal of Social Psychology, 30(2), 255–272.

Gouldner, A. (1960). The norm of reciprocity. American Sociological Review, 25, 161–178.

Graen, G. B., & Uhl-Bien, M. (1995). Development of leader-member exchange (LMX) theory of leadership over 25 years: Applying a multi-level multi-domain perspective. The Leadership Quarterly, 6(2), 219–247.

Guo, L., Decoster, S., Babalola, M. T., De Schutter, L., Garba, O. A., & Riisla, K. (2018). Authoritarian leadership and employee creativity: The moderating role of psychological capital and the mediating role of fear and defensive silence. Journal of Business Research, 92, 219–230.

Harvey, P., Stoner, J., Hochwarter, W., & Kacmar, C. (2007). Coping with abusive supervision: The neutralizing effects of ingratiation and positive affect on negative employee outcomes. The Leadership Quarterly, 18(3), 264–280.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: The Guilford Press.

Hiller, N. J., Sin, H., Ponnapalli, A. R., & Ozgen, S. (2019). Benevolence and authority as weirdly unfamiliar: A multi-language meta-analysis of paternalistic leadership behaviors from 152 studies. The Leadership Quarterly, 30(1), 165–184.

Jiang, H., Chen, Y., Sun, P., & Yang, J. (2017). The relationship between authoritarian leadership and employees’ deviant workplace behaviors: The mediating effects of psychological contract violation and organizational cynicism. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 732–743.

Li, Y., Sun, J., & Jiao, H. (2013). Disintegration and integration: The research trend of paternalistic leadership. Advances in Psychological Science, 21(7), 1294–1306.

Li, Y., & Sun, J. M. (2015). Traditional Chinese leadership and employee voice behavior: A cross-level examination. The Leadership Quarterly, 26(2), 172–189.

Liao, Z., & Liu, Y. (2016). Abusive supervision and psychological capital: A mediated moderation model of team member support and supervisor-student exchange. Frontiers of Business Research in China, 9(4), 576–607.

Liden, R. C., & Maslyn, J. M. (1998). Multi-dimensionality of leader-member exchange: An empirical assessment through scale development. Journal of Management, 24(1), 43–72.

Liden, R. C., Sparrowe, R. T., & Wayne, S. J. (1997). Leader-member exchange theory: The past and potential for the future. Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management, 15, 47–119.

Lin, W., Ma, J., Zhang, Q., Li, J. C., & Jiang, F. (2018). How is benevolent leadership linked to employee creativity? The mediating role of leader-member exchange and the moderating role of power distance orientation. Journal of Business Ethics, 152(4), 1099–1115.

Molm, L. D. (1988). The structure and use of power: A comparison of reward and punishment power. Social Psychology Quarterly, 51(2), 108–122.

Pellegrini, E. K., & Scandura, T. A. (2008). Paternalistic leadership: A review and agenda for future research. Journal of Management, 34(3), 566–593.

Peng, M. W., Lu, Y., Shenkar, O., & Wang, D. Y. L. (2001). Treasures in the China house: A review of management and organizational research on greater China. Journal of Business Research, 52(2), 95–110.

Perugini, M., & Gallucci, M. (2001). Individual differences and social norms: The distinction between reciprocators and prosocials. European Journal of Personality, 15(S1), S19–S35.

Qian, J., Wang, B., Han, Z., & Song, B. (2017). Ethical leadership, leader-member exchange and feedback seeking: A double-moderated mediation model of emotional intelligence and work-unit structure. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1–11.

Redding, S. G. (1990). The spirit of Chinese capitalism. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Scandura, T. A., & Graen, G. B. (1984). Moderating effects of initial leader-member exchange status on the effects of a leadership intervention. Journal of Applied Psychology, 69(3), 428–436.

Schaubroeck, J. M., Shen, Y., & Chong, S. (2017). A dual-stage moderated mediation model linking authoritarian leadership to follower outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(2), 203–214.

Shen, Y., Chou, W. J., & Schaubroeck, J. M. (2019). The roles of relational identification and workgroup cultural values in linking authoritarian leadership to employee performance. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 28(4), 498–509.

Tepper, B. J., Carr, J. C., Breaux, D. M., Geider, S., Hu, C. Y., & Hua, W. (2009). Abusive supervision, intentions to quit, and employees’ workplace deviance: A power/dependence analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 109(2), 156–167.

Wang, H., & Guan, B. (2018). The positive effect of authoritarian leadership on employee performance: The moderating role of power distance. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 357.

Wang, H., Law, K. S., Hackett, R. D., Wang, D., & Chen, Z. X. (2005). Leader-member exchange as a mediator of the relationship between transformational leadership and followers’ performance and organizational citizenship behavior. Academy of Management Journal, 48(3), 420–432.

Wayne, S. J., & Green, S. A. (1993). The effects of leader-member exchange on employee citizenship and impression management behavior. Human Relations, 46(12), 1431–1440.

Wu, M., Huang, X., & Chan, S. C. H. (2012). The influencing mechanisms of paternalistic leadership in mainland China. Asia Pacific Business Review, 18(4), 631–648.

Xu, E., Huang, X., Lam, C. K., & Miao, Q. (2012). Abusive supervision and work behaviors: The mediating role of LMX. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33(4), 531–543.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 71971211) and the Humanity and Social Science Youth Foundation of Ministry of Education of China (18YJC630192).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed significantly to the manuscript. Zhen Wang and Yuan Liu designed the research, collected data and drafted manuscript. Songbo Liu revised the manuscript and provided guidance on the details. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Z., Liu, Y. & Liu, S. Authoritarian leadership and task performance: the effects of leader-member exchange and dependence on leader. Front. Bus. Res. China 13, 19 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s11782-019-0066-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s11782-019-0066-x